One thing we can count on in any ballpark proposal: the grossly inflated numbers projected by consultants.

The Economics

…a study done by Brailsford & Dunlavey shows a new ballpark is expected to produce $12.3 million “in [annual] direct spending for the city and the state.”

“PawSox ownership said one of its consultants, Brailsford & Dunlavey, predicts the state will receive about $2 million in various annual taxes due to the ballpark, and with that, “the net annual cost to the State under the lease/sublease arrangement is estimated to be approximately $2 million.” Providence is projected to see an increase of $170,000 in annual incremental tax revenues.” - RIPR

One thing we can count on in any development proposal: the grossly inflated numbers offered by consultants. Naturally. That’s what they’re paid to do. Likewise, we can always count on the harsh truths offered by independent experts with no clients to please.

Michael Leeds, a sports economist at Temple University, told Southern California Public Radio that the one thing economists can agree on is that sports stadiums have little to no impact on the local economy. “If you ever had a consensus in economics, this would be it.”

“A baseball team has about the same impact on a community as a midsize department store,” Leeds added.

A good rule of thumb that economists use is to take what stadium boosters are telling you and move that one decimal place to the left, and that’s usually a good estimate of what you’re going to get,” Victor Matheson, a sports economist at College of the Holy Cross told SCPR in the same article. Of course this applies to pro sports, so who knows how much less impactful a minor league stadium could be, but Matheson’s math puts Rhode Island tax profits at about $200,000 a year. Not a big dent in the $5 million annual lease agreement that the state will be asked to pay.

The estimated direct spending figure is pegged at $12.3 million a year by the consultants. That’s an estimate of what visitors will spend in the city on game days. (I’d love to see the worksheets for this figure; It sounds like they’re expecting the typical family of 7 from Cranston to get their pre-game, dry-aged porterhouse at The Capital Grille). Applying Matheson’s math to this number adjusts it from consultants range, down to around $1.2 million annually. Again, we’re forgiving the fact that this math applies to pro sports stadiums.

Boosters love to mention the ballpark in Charlotte, North Carolina, as an example of an urban stadium success story. That city’s economic success owes more to the establishment of a popular light rail system that has triggered investment in the city’s core. But if one thing can be taken from Charlotte’s stadium, it’s the financial arrangement under which it was built. The city and county paid a one-time fee of $16 million dollars from hotel taxes, and the franchise picked up the rest. A bit more palatable than the $120+ million that Rhode Island taxpayers will be asked to contribute in the PawSox stadium agreement.

The Truth

If the essence of the PawSox experience could be summed up, it always seems to come back to quality family time out of the house and on a limited budget. It’s a perfect fit for minor league baseball, and maybe that’s why these multi-million dollar spending estimates by the consultants seem so out of place. But even if the PawSox owners are signaling a sea change in philosophy, the experts are telling us the numbers don’t add up. This stadium plan is not a good investment by the state.

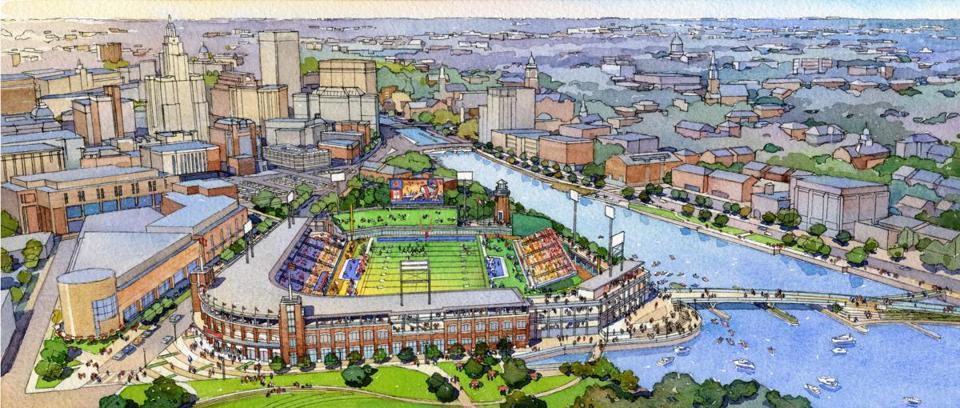

I have a feeling the project is going to get built regardless of public opinion. At the very least Skeffington and the Gang could at least try to make the deal more palatable. Maybe use stadium naming rights to offset the public costs. Maybe the new PawSox owners should approach the Krafts and consider a joint venture in a stadium that splits time with soccer. If not the Revolution, then maybe a minor league team of the Revolution.

The location is the key in this proposal, and frankly, the PawSox need Providence more than Providence needs the PawSox. So If the owners can find more ways to keep their hands out of the video game-burned wallets of Rhode Island taxpayers, all the better.

A Footnote: The Park

The land in the stadium proposal was set aside as a park to satisfy federal land-use requirements in the 195 realignment project. It doesn’t matter how many gumdrop-shaped shrubs you cram along the walkways leading up to the turnstiles, a stadium isn’t a park. Imagine crossing the pedestrian bridge from the East Side to have a picnic in what should be the rolling landscape of a park on the west side, and instead you’re confronted by the cemented “East Entry Plaza.” Not a great place for a picnic. A stadium is not a substitute for open space, and open space is something Providence could use more of. Given the connection to the pedestrian bridge, the central location between the East Side and the “Knowledge District,” (and the complication of the utilities underground), this parcel of land is perfect for it. Students from the proposed nursing school next door could relax here. Waterfire can expand here. Tourists on the Riverwalk can marvel here. Residents can breathe here.

The supporters of this plan rightfully point out that if we build a park instead of a stadium, we’re looking at annual upkeep costs. But park maintenance is a fraction of this stadium’s annual lease, and it’s not difficult to foresee the formation of a group similar to the DID to handle those duties.